Howdy.

Welcome back to what seems to be in danger of becoming a bi-weekly newsletter. My apologies for that. I’ve been a bit busy with pilots, pitches, PROJECT MARBLE, and the Star Wars comic I keep teasing — which will be announced next week at New York ComicCon. Speaking of…

NEW YORK COMIC CON

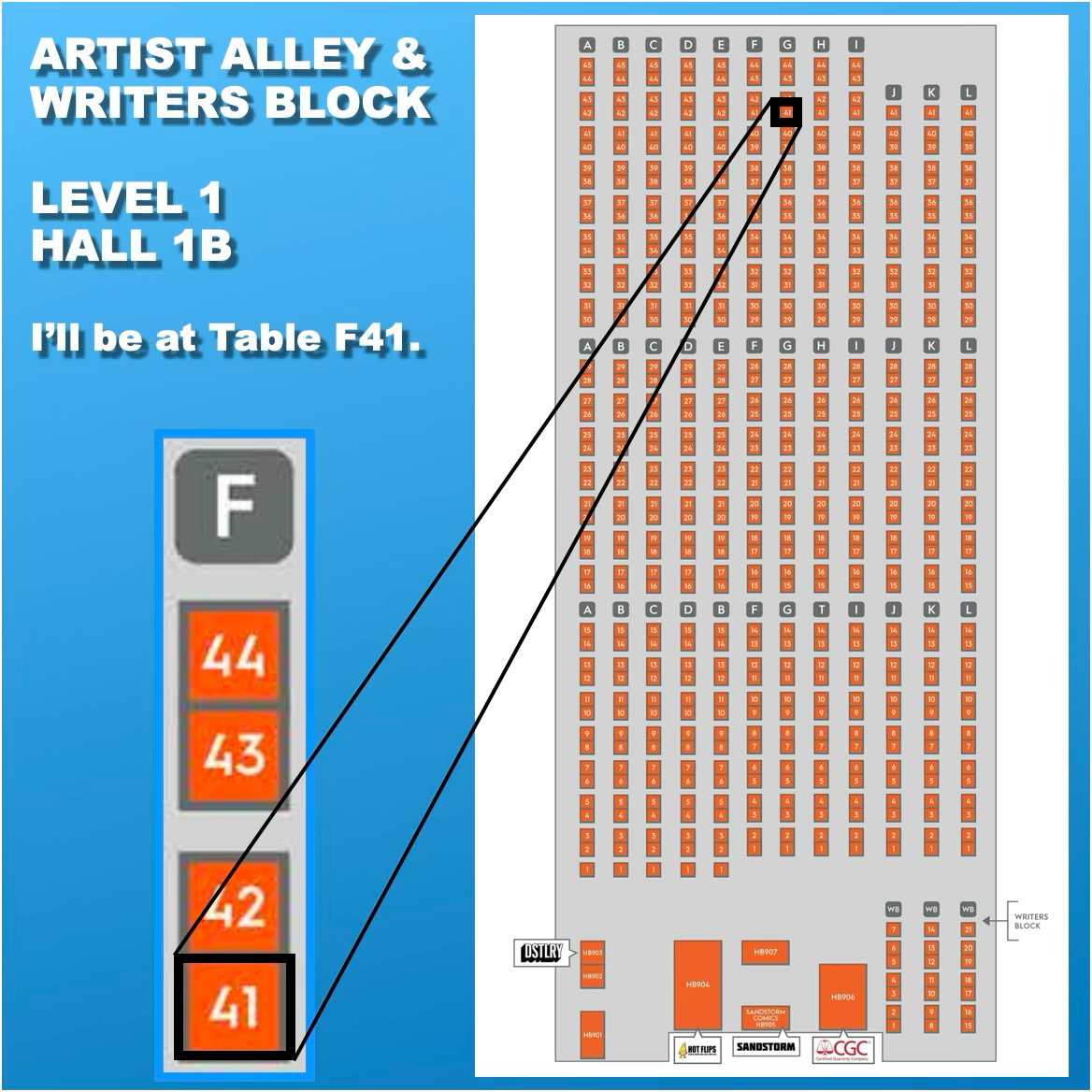

This will be my first year with a table in Artist Alley (which they’re cleverly calling “Artist Alley & Writers Block”). You can find my schedule for this year and where to find me below:

5K

In Any Lifetime recently passed over 5,000 reviews on Amazon (with an average rating of 4 out of 5 stars). Boom.

TOP 10

Collider.com recently published a list of “The 10 Best Superhero Origin Shows.” Click here to see where Arrow ranked. (Hint: It’s #2.)

SHOOTING MY MOUTH OFF

Another newsletter, another edition of all the ways I’ve shot my mouth off over the past two weeks.

First up, we have The Ankler’s Series Business which published an article entitled “'Development is Wage Theft': Pilot Season Death Morphs Into Year-Round Hell.”

Per usual, it’s behind a paywall, but the money quote from me — which I’ll be elaborating on in the next section — is the following:

“Writers didn’t create this situation. We didn’t make development a ‘year-round’ thing,” says Arrowverse co-creator Marc Guggenheim. “We didn’t decide that an entire season of scripts should be commissioned before production could be greenlit. We didn’t decide that showrunners should be treated like feature writers and made as interchangeable as lightbulbs.”

Read the whole thing here.

Last week, I missed getting this newsletter out because I was busy doing a one-day, very poorly publicized (by me — totally my own fault), appearance at Los Angeles ComicCon. While I was there, I did a pretty wide-ranging interview with Brandon Davis. You can check it out below:

THEY DON’T CALL IT “DEVELOPMENT HEAVEN”

The Ankler article I referenced above is about whether so-called “year-round” development has been good or bad for the television business. As with most things, there are two sides to every story, and the issue of infinite development is certainly one with its share of pros and cons.

For those outside of Hollywood, “development” is just a fancy word for “notes.” Execs love to give them. Writers hate to listen to (much less take) them. I was at a birthday party last night, and even though the majority of the crowd were from comic books, you’d be surprised at the number of conversations that turned to the subject of notes in Hollywood. This is unsurprising. If you have more than one writer or more than one creative executive or some combination thereof in a room together, I guarantee that within 15 minutes (i.e., after the election discussion is exhausted), the topic of conversation will turn to that of notes. No one is happy with the system as currently constituted. Writers aren’t. Executives aren’t.

More than once, I’ve had a director sit in on a script call for a television episode, and every single time their reaction was, “Oh my god. This is what you have to deal with?”

Yeah. Every episode.

And it’s not the executives’ fault. They don’t like this system either. They don’t like having to justify their jobs with pointless notes. They don’t like coming up in a system where they learned bad habits from their predecessors. They don’t like living in constant fear of losing their jobs due to a cycle of corporate layoffs that is as endless as development seems to be this day.

I like to think that I can offer something of a unique perspective in that I work in a variety of different mediums: film, television, comics, prose. Of course, I get notes on all my projects, but the television notes are just… different. And I don’t think the difference depends on who’s giving the notes. I truly believe that the difference lies in the system in which television is developed and produced. Particularly lately.

I’ll share a vexing example. For every pitch I do, I write up a little script for myself. Rather than pitch the revised pitch back to the studio where the project is set up, I just emailed over my “script” — with its huge font size and the seemingly idiosyncratic bolding and highlighting I do because the thing is designed to be a safety blanket for while I’m pitching. It’s really not meant to be read by other eyes.

Anyway, because I had emailed a document, the Laws of Hollywood required that the execs receiving it MUST give notes as surely as day follows night. And that’s, y’know, fine. I always say that I write for free but get paid to take notes. But this is development and, as such, I’m not yet getting paid. Still, I’ll take a good note from anyone. Who doesn’t want to make the thing — whatever the thing may be — better, right?

The problem is that we (i.e. everyone working in television) have lost the plot. Because we’re talking about a pitch, the only — ONLY — notes that are relevant are: (1) Notes that will prevent a potential sale turning into a pass; and (2) notes that might make a likely pass into a potential sale. Can we all agree that nothing else matters at this stage?

Evidently not. But the point is that the system is so broken, notes are given and taken without any regard for what their actual purpose is. We’ve lost sight of why there is a notes process in favor of all of us surrendering to the fact that there just is a notes process. And it’s making everyone, writers and executives alike, testy — particularly now when employment for everyone is so rare and tenuous.

I think I kinda sorta know how we got here. As that Ankler piece notes, “There are people who made their money off of writing really shitty fucking scripts” according to one studio exec. A showrunner in the article admitted that “some shows could have used more time in the oven.”

I don’t disagree.

In a recent interview with The Hollywood Reporter, writer/actor Brett Goldstein (of Tel Lasso fame) noted what most showrunners looking to staff up their shows learn: “Most scripts are fucking dog shit.”

Let’s, for a moment, assume Brett is correct: The vast majority of scripts are just plain bad. Now further posit that the development system has evolved to deal with the vast majority of scripts; that the development process isn’t a bespoke institution but rather more of a “one size fits all” kind of operation.

Imagine a machine that takes a raw, unformed piece of metal. You put the metal in, and the machine forges it into a widget. Great. Now take a widget and put it through the machine. What you get on the other end doesn’t look like a widget anymore. I’ve come to wonder whether the development process in television has evolved into something like that: A system designed to improve horrible scripts but which has no idea what to do when presented with something that’s competently written — and in an atmosphere of such fear that evaluation between the two is virtually impossible.

Be good to each other.

Best,

Marc

10.11.24

Encino, California

A very interesting perspective on the “notes” system. I agree with you one hundred percent. Arrow being number two on that list is pretty good, but it’s my all time favorite origin story and series in general, so number one on my list. I always love hearing anything Arrowverse related. Congratulations on the success of your book! It is well deserved.